The Ultimate Guide to Quality Investing

An introduction to quality investing. Why does quality even matter?

Introduction

The point of this article is to provide a primer on quality investing and a criteria or checklist to evaluate when finding great companies within the vast stock market.

Quality investing

Quality investing is the intersection between value and growth investing.

It inherently accounts for value and growth’s respective weaknesses and takes advantage of this by having a long-term view in the market. Quality investing simply involves investing in wonderful businesses that will compound their value over sustained periods of time.

What are quality compounders?

We view quality compounders as high-quality companies who can consistently generate a high return on its capital because they are protected by economic moats throughout the entire business cycle. Some economic moats include (we will discuss these soon):

Vast and reinforcing network effects

Switching costs

Strong brands

Quality compounders also possess characteristics such as:

Pristine balance sheets

High returns on capital

Long runway of growth and reinvestment

Recurring or diversified streams of revenue

Pricing power

Market leaders in their respective industries

These companies are also run by honest and competent managers that deploy capital prudently and effectively to maximize the intrinsic value of the company in the long-term.

The key to successful compounding involves three components. These are:

Reinvestments back into the business

High returns on capital on these reinvestments

Durability of these returns on capital

This demonstrates the drastic difference of a company’s stock price return depending on whether the company possesses a high ROIC compared with those who produce a low ROIC. As illustrated in the graph, companies with a higher ROIC have substantially outperformed their low ROIC peers, which only further converges as time increases.

However, the return on capital metric we prefer to use is the cash return on invested capital (“CROIC”). The equation is as follows:

We prefer using the CROIC over ordinary industry metrics such as the ROIC, ROE, ROCE, and many other metrics due to the fact that the free cash flow figure is the most representative of the cash generative capabilities of a company compared to conventional accounting metrics such as EBITDA that may be misleading.

An example of a company with a strong CROIC is Visa Inc., earning a mouthwatering CROIC of 32%:

This means that for every $100 Visa deploys as reinvestments, Visa will get back $32.

However, basic economic theory teaches us that these high returns on capital a business earns will eventually attract competition that will slowly erode away these returns until it reverts back to the ‘mean’. This theory is called reversion to the mean. It is a very solid theory, but in reality, it does not apply to quality companies at least for a sustained period of time.

Quality companies are protected by economic moats that retain these high levels of return on capital.

Economic Moat

As many investors know, an economic moat is crucial in long-term investing as it protects the company from competition, maintains its high returns on capital, and hence, its future earning power for a sustained period of time.

But there are two characteristics to evaluate in a company’s durable competitive advantage. It is the:

Strength or size of the moat

Trajectory of the moat

Strength of the Moat

There are many ways to categorize strength and sizes of economic moats. Some can fit together as a single category, while some can be argued to be its own category.

Network Effects

A network effect is when the value of a product or service increases to all participants with each incremental user joining the network. With more existing participants on the network, the more lucrative the network becomes for new users.

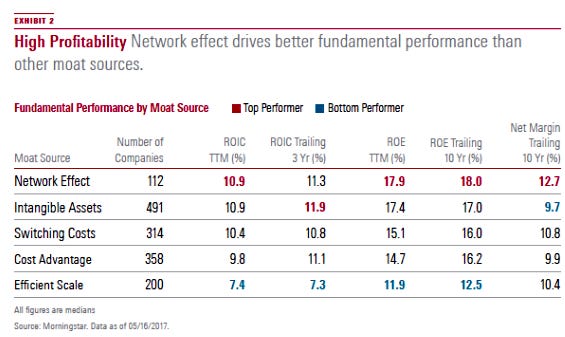

Based on Morningstar, this type of moat is statistically the most durable and enduring moat based on long-term historical returns of companies that possess network effects:

Once a successful and reinforcing network effect is established, companies can benefit from high returns on capital, they generally have wider margins from less incremental capital needed to maintain the network effect, and network effects usually have the highest longevity out of any moat.

Take a look at Meta’s network effect as more of the world population joins one of Meta’s services as evidenced by its Daily Active People (DAP):

Humans are inherently social creatures who care about their social class, appearance, and ultimately how they are judged by their peers around them. This social phenomenon has allowed Meta to build not just one, but a few top social media apps that are used by billions around the world.

Network effects are most prominent in technology, financial services, and consumer discretionary companies.

Some companies that possess network effects are: Meta, Copart, and Visa.

Switching Costs

High switching costs refer to the high costs that arise from changing from one product or provider to another.

Switching costs can manifest due to a number of reasons:

No cheaper alternatives in the market

No better alternatives

No easy way to change to an alternative

Companies who have high switching costs generally are protected by monthly or annual subscription plans, long-term binding contracts, or the product or service that it offers is mission-critical to the customer. The best companies usually have two of these listed attributes.

Ideally, the strongest companies that have highest switching costs offer business-to business (B2B) software-based services that are mission-critical and charged on a monthly or annual recurring subscription plan. Why is this the best scenario? It is because:

Businesses are often slow to change their everyday workflow software

Businesses are not incentivized to change this software if it is mission-critical

Software solutions are easy to distribute, maintain, and update for the customer

Software that is already embedded into a company’s workflows are often very hard to replace with a substitute or competitor (higher cost to change to a cheaper alternative)

Unlike consumers, businesses are not swayed by preference or trends and mostly do not default on their payments

Retention rates are often a strong indicator of a business’ switching costs. Take a look at MSCI’s retention rates over the past 5 years:

A steady retention rate is a strong indicator of switching costs, as represented by the illustration of MSCI. On the other hand, a decreasing retention rate over the years is a sign of a low switching cost company as customers are able to leave as they please.

Some companies that possess high switching costs are: Intuit, Microsoft, and MSCI.

Brands

Strong brands are company recognizable brand names or logos that elicit the same feeling or emotion to most, if not all customers of the company.

Strong brands can also command higher prices on their products or services.

A great example of a company that has a strong brand is Apple. Rather than being perceived as a consumer technology company, it is actually mostly perceived almost as a consumer discretionary company given how common the iPhone is among the world population. The Apple logo represents feelings of a premium product, trust, loyalty to the customer.

The brand loyalty of Apple customers have grown to a very strong level over the decade. Apple users may, in some cases, socially distance themselves from users who do not own an Apple iPhone, and part of this has been known as the "Green bubble, blue bubble” phenomenon, where texts shown in blue signify an Apple iPhone user whereas a text in green shows that the user is an Android user.

Over time, customers of strong brand companies will experience some form of high switching costs.

Some companies that possess strong brands are: Hermes, Ferrari, and Apple.

It is important to note that companies usually possess more than just one moat, and it is always difficult to categorize moats. For example, Google has a strong network effect as the more user searches create more data which leads to more accurate algorithms that will yield better future results for both existing and new users. Yet, the world ‘Google’ has become used as a verb in itself, suggesting a strong brand.

The most important part of this process to take away is to extensively study the company to come to a conclusion as to whether future returns on capital will be eroded or not. If not, why is this the case?

Trajectory of the Moat

The strength or size of the moat is important, but so is the trajectory. After all, the size of a business’ moat is based on the past, whereas the trajectory is based on the future, which makes the trajectory of the moat arguably more important for investors to consider.

“Leaving the question of price aside, the best business to own is one that over an extended period can employ large amounts of incremental capital at very high rates of return.”

— Warren Buffet, 1992 Shareholder Letter

What translates to earnings growth? It is simply:

Hence, the intelligent quality investor will conclude that any business that attempts to boost either component will translate into long-term earnings growth.

There are generally two types of wide-moat companies. These are the ‘Legacy Moat’ companies and the ‘Reinvestment Moat’ companies.

What are Legacy Moat companies?

These are wide moat companies that do dominate the industry they operate in and have earned high returns on capital in the past, but do not have any accretive opportunities to deploy incremental capital at similar historical rates of return.

Some examples that come to mind are Coca Cola, McDonald’s, and Hershey. These were of course great businesses, but their best days are likely behind them.

Because these companies suffer from a lack of reinvestment opportunities, a majority of future earnings growth generated is distributed back to shareholders in the form of dividends or buybacks. This means that these Legacy Moat companies eventually transform into the equivalent of a high-yield bond that should grow slightly faster than the average high-yield bond for the investor.

They are, by name, ‘legacy’, as their business quality has deteriorated from a lack of reinvestment opportunities that once generated high returns on capital. This is natural given that as a company grows, it will be much harder to find opportunities that will return similar growth rates at a larger capital base. This is what we are currently seeing with the market’s worries toward Big Tech’s significant increases in CapEx to facilitate AI growth.

Consequently, if the investor were to purchase shares in these Legacy Moat companies, the investor would likely not achieve the same stellar historical returns in the past going forward. This is solely due to the fact that their high return on capital is based on the past investment returns, not incremental investments going forward.

What are Reinvestment Moat companies?

These are wide moat companies that have a proven track record of earning high returns on capital, and still have enthralling opportunities to reinvest incremental capital at high rates of return. As a result, instead of distributing a majority of earnings back to the shareholders like Legacy Moat companies, these companies can reinvest back into the business at high rates from a long runway of future reinvestment opportunities that will achieve the full compounding effect for the investor in the long-term.

Some examples of companies that share these attributes are Amazon, Constellation Software, and Dino Polska.

Consider two companies over a 10-year horizon: The first company, Reinvestment Moat Co., is a Reinvestment Moat company that has the ability to reinvest 100% of its earnings at a 20% ROIIC. The second company, Ordinary Co., is an ordinary company that most retail investors would decide to invest in. It reinvests 50% of its earnings back into the business and distributes the other half directly back to shareholders as dividends.

However, Reinvestment Moat Co. trades at an optically high multiple of 20x compared to Ordinary Co.’s 10x, that is double the multiple. Take a look at the following table:

This table illustrates that, despite paying a higher initial multiple and the multiple actually contracting by the end of the investment period (Year 10), the total return of Reinvestment Moat Co. significantly outperforms Ordinary Co.

Despite all the lucrative dividends paid out to shareholders over the 10-year period, Reinvestment Moat Co. was actually the undervalued company hiding in plain sight over an optically cheap ordinary company like Ordinary Co. This illustration is analogous to the late Charlie Munger’s famous quote:

“Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return – even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result.”

— Charlie Munger

Clearly, many investors underappreciate the nature of Reinvestment Moat companies, like its long runway of growth, yet, many still prefer investing in companies like Ordinary Co.

The key to investing in Reinvestment Moat companies is not the specific growth rate forecasted for next year, but instead having a strong conviction that there is a very long runway of growth and that the moat will remain enduring as time grows to produce those high returns on capital. The focus is to not on quarterly or annual figures but to visualize if the company is able to be worth 10x in a decade or longer.

This means the investor has to create a very high hurdle rate and only accepting the top 0.1% of companies to fit the criteria of a Reinvestment Moat company and allocating capital to these very few, select companies.

What are Capital-light Compounders?

It can also be argued that there is actually a third category of wide moat companies known as ‘Capital-light Compounders’.

These Capital-light Compounders generally possess a mix of both Legacy and Reinvestment Moat companies. As suggested by the name, these companies are capital-light to maintain and operate largely due to underlying business model advantages, such as being a software company or financial services technology company that operates in horizontal markets. As such, they have a large total addressable market (TAM) where they only capture a small percentage of this market, further suggesting a long runway of reinvestment. However, they often distribute a large portion of earnings to shareholders in the form of buybacks or dividends, akin to Legacy Moat companies, largely due to how much cash generative the business model is.

Capital-light Compounders earn royalties or fees from platforms online they operate from intangible assets, such as branding or use of intellectual property. But with minimal reinvestments, how do these companies grow earnings or FCF? They actually defy the equation we learned above.

The caveat is that most Capital-light compounders have high pricing power—the ability to raise prices without affecting demand at a rate higher than inflation—to accommodate growth. Pricing power is perhaps one of the most important factors to successful compounding. Pricing power is related to a concept taught in economics known as ‘price elasticity’. This is a measure of the degree to which individuals, consumers, or producers change their demand or the amount supplied in response to price changes. If a company’s customers are not price sensitive, a company can triple the price charged with minimal change in sales.

If there are a limited number of substitute products and competitors, companies tend to have strong pricing power. This is why finding great businesses that operate as monopolies or oligopolies in their respective industries are important. However, to be able to have pricing power in the first place, companies not only must dominate their respective industry but they must provide a product or service that is mission-critical and essential to their customers. This way, customers will always have a need to continually use the product or service especially since this product or service provides a value much greater than the price paid. Businesses that offer such mission-critical products or services typically operate in the business-to-business (B2B) line as businesses are less willing to change the way they operate as opposed to rapidly evolving consumer behavior and trends.

Not only do Capital-light compounders benefit from volume growth from a huge TAM, but also pricing growth as a tailwind to earnings growth. Typically, Capital-light compounders have latent pricing power and will only grow pricing if necessary to avoid unwanted attention from regulators. If a year has a slowdown in volume growth, these companies can grow their earnings per share just from price increases alone.

Some examples that come to mind are Visa, Mastercard, and Fair Isaac Corporation.

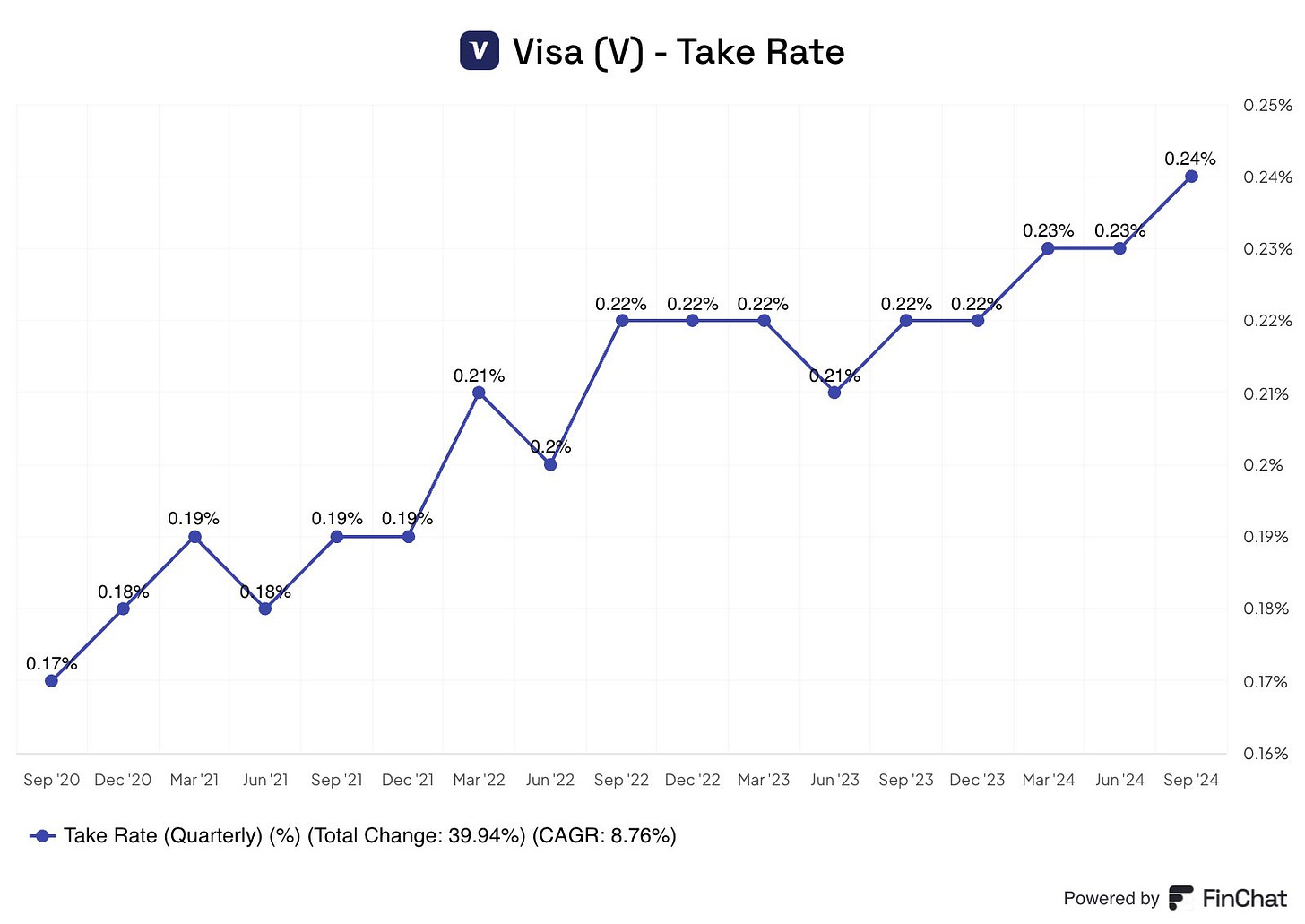

To show a real-world example of both volume growth and pricing growth, Visa is a great example:

Volume growth — expressed in total payment volume (TPV)

Pricing growth — expressed in take rate %

As illustrated in the graphs and tables above, since FY2020, Visa has experienced volume growth by almost an increase by +538% (!) completed with pricing growth of +40% (!) within around the same period. As such, Capital-light compounders are able to grow from both large volume increases and price increases along the way.

It is important to note that while volume growth is generally easier to spot, pricing growth is much more challenging. Companies that are monopolies or oligopolies in their respective industries will not openly disclose their pricing power to the public. If they were to do so, it would attract public scrutiny, fines, and regulations from the government. Hence, it is the job of the intelligent quality investor to read between the lines and figure out a method to evaluate the extent of a company’s pricing power. It is not always easy.

Capital-light Compounders also have much control over their own destiny. Because they are the dominant leaders in their respective industries, they are able to control their business growth metrics internally given their market power.

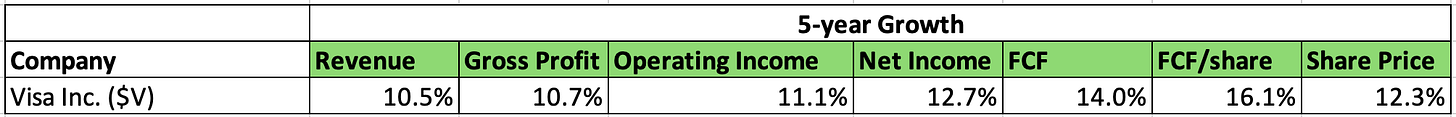

Take a look at the following illustration of Visa’s growth metrics over a 5-year period (inspiration idea taken from a fellow quality investor, Long Equity on Twitter):

Visa’s gross profit grows faster than revenue as companies are able to expand their margins by charging a higher price (pricing power).

Operating income grows faster than gross profit as companies are able to reduce operational costs, such as R&D, sales, marketing, and administrative matters (operating efficiency).

Free cash flow grows faster than net income as companies are able to manage their cash more effectively and reduce CapEx over time (cash conversion).

Free cash flow per share grows faster than free cash flow simply from allocating cash towards buying back more stock (share buybacks).

Share price grows faster than free cash flow per share (usually) from a change in the valuation of the quality of those free cash flows (multiple expansion).

Because of minimal reinvestments back into the business, Capital-light Compounders are share cannibals of their own stock, which raises the free cash flow per share. Essentially, if earnings growth is 12% per year, rather than intrinsic value growing 12% per year it is accompanied by earnings deployed into share buybacks of 3% which raises the intrinsic value growth to 15%.

Also notice how share price appreciation grows faster than free cash flow per share only ‘usually’, because the market may not accurately assign the correct multiple on those cash flows at all times. The market fluctuates on a day-to-day basis in the short-run, but the multiple should correct itself to a more accurate outlook in the long-run. In this case, there is a large differential between Visa’s free cash flow per share growth and its share price appreciation. This may suggest that Visa’s share price is currently undervalued due to the fundamentals improving but the share price not keeping up, but there may always be underlying issues lurking. It is best to explore reasons why there is such a differential and whether it is simply just noise rather than a fundamental issue.

Conclusion

There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ choice when it comes to investing, but the intelligent quality investor should lean more towards companies that have a Reinvestment Moat or are Capital-light Compounders. This would maximize both ROIC and the Reinvestment Rate to the fullest extent. In reality, no one company fits one category and is always a mix of both.

Ultimately, it is in the best interest of the intelligent quality investor to find both a wide and widening moat company. Many focus on the size of the moat, but not many focus on the trajectory of the moat (which is arguably more important for the future).

Quality of management team

When seeking a quality compounder, we view that a great management team, run by honest and competent managers, can boost a company’s shareholder return materially in the long-term.

Take a look at two wonderful companies: Alphabet (Google) and Amazon. Both business are software-based and require very few assets to run. Both have various successful and cash-generative services, such as Google Search, YouTube, Google Cloud Platform for Google, and E-commerce, AWS, and advertising for Amazon, to name a few.

However, Amazon has outperformed Google for the past 20 years. Why? The quality of Amazon’s management is far superior than Google’s. While both companies spend billions in ambitious projects to innovate, Amazon’s spending habits are much more financially ‘intelligent’ historically. Google has spent billions into speculative ‘moonshot’ projects (labelled “other bets”) that have led nowhere whereas Amazon’s ‘other’ category were targeted into secular, technological trends that have been proven to be great business segments. An example would be Amazon’s advertising business that used to be categorized as ‘other’, but has grown so large that it now has a category of its own in Amazon’s financial reports today.

Yet, despite a lack of quality in Google’s management team, Google’s stock has still managed to outperform the index by a wide margin. Why? Because of the superiority of the business quality. This demonstrates that business quality is the most important characteristic of an investment despite a lower quality management team.

We judge management quality based on a proven track record that has demonstrated a history of seeking to produce both strong free cash flow generation growth and quality in those cash flows.

An incentive structure or program is an additional admired trait found in great management teams.

“Show me the incentive, and I will show you the outcome.”

— Charlie Munger

An example of a compounder with such an incentive program in a serial acquirer is Constellation Software, a leading provider of vertical market software (VMS) that focuses on continually acquiring VMS businesses to provide mission-critical solutions to public and private clients around the world.

Constellation Software employs a unique and highly effective bonus scheme designed to align employee incentives with long-term shareholder value creation. Under this program, employees receive bonuses based on the ROIC generated during a business period. These bonuses are paid in cash but are specifically earmarked for the purchase of Constellation Software shares in the open market, with the requirement that these shares be held for approximately 5 years. Executive officers are required to invest 75% of their after-tax incentive bonus into Constellation Software and held in escrow for a minimum of 4 years. This structure ensures that employees and managers are directly incentivized to focus on value-accretive acquisitions, avoid overpaying for deals, and consistently meet the company’s stringent internal hurdle rate, which is set at 15-20%. By tying compensation to both ROIC and long-term equity ownership, the scheme fosters a culture of disciplined capital allocation and aligns the interests of employees with those of shareholders.

Its founder, Mark Leonard, has also reduced his salary to zero and lowered his bonus in 2014. Leonard’s decision to forgo his salary and reduce his bonus is emblematic of his broader leadership style and has fostered a culture of accountability and trust within the organization. This approach has not only reinforced the company’s commitment to sustainable growth but has also set a high standard for corporate governance that distinguishes Constellation Software from many of its peers in the software and private equity industries.

“Cutting my compensation will allow me to lead a more balanced life, with a less oppressive sense of personal obligation. I'm paying my own expenses for a different reason. I've traditionally travelled on economy tickets and stayed at modest hotels because I wasn't happy freeloading on the CSI shareholders and I wanted to set a good example for the thousands of CSI employees who travel every month.”

— Mark Leonard

For acquisitive-driven compounders known as ‘serial acquirers’ like Constellation Software, a strong incentive program contains targets pertaining to a high ROIC or strong organic growth. These two traits are the most important key performance indicators to view in a serial acquirer that will ultimately drive the compounding effect that ordinary acquisitive companies generally do not have.

The opposite is also true. Greedy, incompetent management teams can erode business quality by supporting decisions that favor their internal targets or incentive programs that benefit their individual self. This can be in the form of boosting an individual quarter or fiscal year’s EPS in the short-term at the expense of shareholders or the long-term prospects of the business that are much more valuable.

An alarming red flag of poor management is when executives prioritize attracting investors or securing external funding over enhancing the quality of the business. This misalignment often manifests in a neglect of critical drivers of long-term value creation, such as sustainable free cash flow growth, superior return on capital, consistent organic growth, or the strengthening of the company’s competitive position within its industry. A robust management team, by contrast, focuses on widening the competitive moat and reinforcing the company’s market leadership, rather than pursuing short-term financial engineering or dilutive capital raises that may erode shareholder value over time.

It is crucial that when looking for compounders, the managers that run the companies fall into the former characteristics and not the latter.

An example of a company that we deem as well-run by a disciplined management team is Dino Polska, found in Poland. Dino Polska operates as a leading grocery retailer, focusing on proximity supermarkets in rural areas, a strategy that has allowed it to grow from 111 stores in 2010 to over 2,500 by mid-2024, achieving a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 25%. The company’s management, led by founder Tomasz Biernacki, has demonstrated a long-term orientation, prioritizing sustainable growth over short-term gains. This is evident in their decision to own 95% of their store locations, a long-term capital-intensive strategy that reduces costs and provides full operational control, rather than leasing properties, which is more common in the industry but costly in the long-term.

The management team’s discipline is further demonstrated in their focus on standardization and efficiency. Every Dino store is built to the same specifications with approximately 400 square meters with 5,000 products to ensure consistency and predictability in its operations. This standardization, combined with in-house construction through their subsidiary Krot-Invest, allows Dino to maintain control and reduce costs, contributing to a higher return on invested capital (ROIC) than its competitors. Additionally, the company’s vertically integrated meat processing plant, Agro-Rydzyna, ensures high-quality fresh meat offerings, a key differentiator in the Polish market, where consumers prefer fresh over packaged meat.

This cost-consciousness mindset extends to their management practices, with fixed salaries for executives capped at 10 times the average employee’s salary. Furthermore, Biernacki owns ~51% of the company. This substantial ownership stake ensures that Biernacki’s incentives are closely aligned with the company’s performance and value creation over time. Such a high level of insider ownership is a strong signal of confidence in the business, as it demonstrates that the founder has "skin in the game", and reduces the risk of short-term decision-making or actions that might prioritize immediate gains over sustainable, long-term growth.

Dino Polska exemplifies a well-run management team through its long-term strategic focus, disciplined capital allocation, and operational efficiency. These qualities have enabled the company to compound shareholder value, making it a standout example of a high-quality compounder in the retail sector.

We also find that a great sign of management quality is through any public writings or interviews. Although rare, they usually show whether a manager is a committed, honest, intelligent, and intentional manager that runs the business. Instead of focusing on short-term targets like sales growth or EPS growth, managers that mention words or phrases, such as “return on capital”, “free cash flow per share”, and “long-term”, can demonstrate their approach towards maximizing shareholder value. Take a look at Amazon’s classic 1997 shareholder letter by Jeff Bezos:

Some keywords and phrases to highlight from his 1997 Shareholder Letter:

“We believe that a fundamental measure of our success will be the shareholder value we create over the long term.”

“Returns on invested capital”

“We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions.”

“When forced to choose between optimizing the appearance of our GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we'll take the cash flows.”

Upon further research on Amazon’s ex-CEO, Jeff Bezos, one would come across that Bezos was once working at a hedge fund. As a result of past experiences, Bezos understands what to do and what not to do as a business owner.

Rather than conforming to the irrationality of Wall Street estimates and targets, Bezos instead recognizes to reinvest Amazon’s earnings into the future for a higher upside in the form of market leadership, greater profitability, and higher returns on capital. This strategy has unsurprisingly worked out well.

Not all CEOs today write personalized shareholder letters, but those who do stand out vastly to the intelligent quality investor and investors can rest assured knowing that any execution risk is minimal and the capital that is being employed is investing into quarters and years into the future that will grow the company’s intrinsic value.

Some of these examples illustrated are a lot more qualitative than quantitative, so there is no one ‘checklist’ when assessing management quality. This is where the investor has to read between the lines and understand the company inside-out to truly gauge management quality.

But remember: business quality trumps management quality. As Buffett said:

“I try to invest in businesses that are so wonderful that an idiot can run them, because sooner or later, one will.”

— Warren Buffett

Ultimately, it is paramount that a quality compounder is not only carried by their robust business models but also well-run managers that are disciplined in their capital allocation to increase the intrinsic value of the company in the long-term.

Constructing an Investable Universe

When it comes to quality investing, there are only a handful of industries or sectors that are economically sound and viable that produces wonderful businesses to pass the first hurdle of a quality criteria (and the most important one) which is business quality. It is the job of the intelligent quality investor to narrow down the companies one will ever invest in. The following are sectors or industries that are viewed favorably in terms of returns on capital, economic moats, and business models (to name a few):

Technology Software / IT (such as — Microsoft, Amazon, Meta)

Financial services (such as — Fair Isaac Corporation, S&P Global, MSCI)

Payments (such as — Visa, Mastercard, Adyen)

Semiconductors (such as — ASML, KLA Corporation, TSMC)

Cybersecurity (such as — Fortinet, Qualys)

Insurance (such as — Kinsale Capital Group, Brown & Brown)

Luxury (such as — Hermes, Ferrari)

Serial acquirers (such as — Constellation Software, Lifco, Lagercrantz)

It is interesting that not every company fits into one category of a sector or industry. This is due to the sheer fact that quality companies are larger in market capitalization and operate many business segments with optionality. For example, Copart could be viewed as an industrials company because it deals with totaled vehicles but operates an online auction platform that collects fees from exchanges. This could also make it a technology company. Regardless of this, the intelligent quality investor should not focus on industries or sectors but on individual companies and their underlying fundamentals.

Most of the time, when seeking for quality compounders, the investor will notice that it is rare to find such companies that meet all three criteria: business quality, management quality, and trading at a fair price.

This is where a watchlist comes into handy. Often, quality compounders trade at expensive levels (and they are expensive for the right reasons), so price is the only considering factor before making the investment. The intelligent quality investor will acquire shares in these compounders when the right time arises. This can be in times of broad market crashes to even company-specific negative news, such as an over-exaggerated earnings result that misses Wall Street estimates by a small margin. In these points of crises are where the money is made.

We view the following names as worthy of the title of quality compounders (to name a few):

Fair Isaac Corporation ($FICO)

Visa Inc. ($V)

Copart Inc. ($CPRT)

Microsoft Corporation ($MSFT)

Amazon Inc. ($AMZN)

For more information on Amazon Inc.’s business quality and what makes it a quality compounder, we have published a deep dive linked below:

Deep Dive - Amazon.com

(Disclosure: All of this information is at the time of this writing. I am currently long )

These are just some names of companies we view as quality compounders within our investable universe. It is always important to do your due diligence to find out whether certain sectors or companies fit within your own quality investable universe. As mentioned, quality investing ensures a strict standard, thus, some investors may view a company favorably while others may not.

Mistakes, Misconceptions, and Red Flags

Dividend payouts

While a company paying out a share of its earnings as dividends directly back to shareholders can serve as a form of passive income, it can often be a mistake for said company to do this.

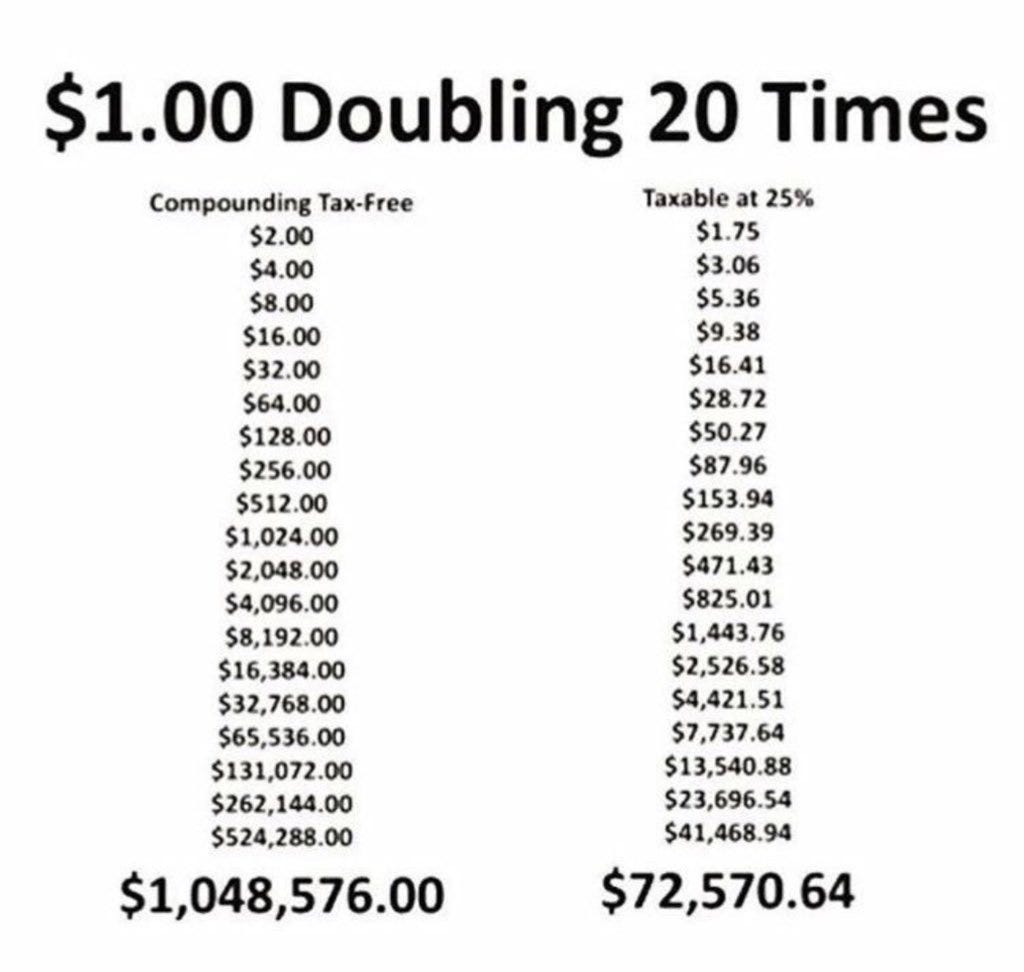

First of all, the payout of dividends significantly slows down the compounding process of reinvested earnings back into the business. Take a look at this illustration of taxes on the effect of compounding, which illustrates the same idea:

Furthermore, dividends are inefficient as they are often double-taxed—meaning that not only are the company’s profits taxed from the very beginning (corporate taxes), they are also taxed on the shareholder by a withholding tax by the U.S. government. This ultimately slows down the compounding effect significantly in the long-run.

If a company were to increase the shareholder yield (buybacks plus dividends), it would be wiser to buyback stock than increase the dividend payout. Generally, quality compounders are optically expensive at first glance in the short-run, but are terminally undervalued in the long-run.

Market Capitalization

Most quality investing involves creating an investable universe around high-quality stocks, and by definition, this typically means a universe of mostly mid-large capitalization companies and above.

For reference:

Small cap: $300 million - $2 billion

Mid cap: $2 billion - $10 billion

Large cap: $10 billion - $200 billion

Mega cap: $200 billion and above

While many criticize that companies that are large in market capitalization have little upside to grow, this is almost always false and is not a good predictor of future returns.

Ten years ago in 2015, Apple was the largest company and most doubted the company’s growth profile going forward. Today, Apple is worth $3.68 trillion, +735% the size ten years later despite its enormous size previously.

Of course, some might call this example cherry-picking by pointing out that most of the top 10 companies from decades ago have fallen of the list. This is true. But what is also true is that much of Apple’s performance has been backed by solid fundamental improvements in the business to support the stock price performance while many of the previously largest companies were cyclical in nature and its stock price faltered as fundamentals faltered too.

What most small cap investors do not realize is that often the next Meta or Amazon is merely just Meta and Amazon itself. Both have significantly outperformed the S&P500 backed by strong and growing fundamentals.

The logic behind larger market capitalization companies is that they are generally larger for the right reasons. They are much more entrenched and dominant in their industries, have a longer track record to show for predictability, and are more cash generative compared to smaller capitalization companies. It does not make sense to solely conclude that a larger market cap company has less upside than a smaller market cap company when one is comparing between apples and oranges.

In fact, the longer a company has been around for, the longer it will be around for. This is also supported by the Lindy Effect, which we discussed in our Ferrari Deep Dive, which you can read below:

In quality investing, the focus is on competitive advantages, strong fundamentals, and predictability. Large caps with durable moats can continue compounding returns over time, making them just as viable, if not more so than smaller, riskier companies that have little to show in their track record for long-term investors. If a large or mega cap company can grow earnings by 15%, even at that scale, it should not matter what the size is. The intelligent quality investor should not limit oneself to a certain market cap range or limit.

Healthcare sector

While the healthcare sector as a whole is not totally uninvestable, around 99% of all healthcare companies are likely to be uninvestable for the quality investor.

This is because of the enormous regulation intact with each product in its research, development, and release phases.

Biotech companies are even more uninvestable for the quality investor. There are typically four clinical trial phases that a biotech or drug company has to go through and pass in order to successfully market the drug:

Success rate = (1 - 0.97) x (1 - 0.95) x (1 - 0.88) x (1 - 0.46) = 0.00972%

In other words, the chance for a drug to market after passing all clinical trial phases is a 1 in 10,000.

The biotech sector is simply not predictable enough for the intelligent quality investor to invest in. Research and development for new drugs takes an enormous amount of time, capital or funding, and expertise to achieve an outcome with no level of certainty in sight. Of course, the reward is staggering, but the permanent loss of capital is likely to be of greater chance at the end of the investment period. The advise would be to stay out of biotech entirely.

Some quality names that may be of usefulness in the healthcare sector are:

Medpace Holdings

Mettler-Toledo

Novo Nordisk

IDEXX Laboratories

Zoetis

Attention to the Macroeconomics

Investors are continuously bombarded with macroeconomic news everyday from the largest business news agencies, such as CNBC and Bloomberg. Quality investors do not focus much of their attention on macroeconomics or the current affairs in the economy because:

It is hard to predict what will happen

It is hard to predict when it will happen

It is hard to predict the effect it will have on great businesses in the long-run

A great example to depict this is the year of 2020. A global pandemic, COVID-19, forced lockdowns that disrupted the global economy, trade, and daily business operations around the world.

Hypothetically, if you knew the events from the start of 2020 onwards, such as:

The COVID-19 pandemic that closed the global economy

Ukraine-Russia War

Israel-Hamas Conflict

Higher interest rates

Would you have been quick to sell? Most likely. In hindsight, however, the S&P500 returned around a 13% CAGR over the past 5 years, almost double your return despite the terrible events that have occurred (this is at the peak before COVID-19 sent the markets down 30%).

The following is an illustration that best depicts this:

Stock-based compensation (SBC)

Stock-based compensation (SBC) refers to a system where companies reward employees by providing shares of the company as part of a compensation package to incentive performance and align employee interests with those of the shareholders.

A good example of a company with high SBC that can be deceptive if not investigated further is Palantir:

Over the past 5 years, Palantir’s SBC has greatly negated any free cash flow generation from the company. While it is true that in today’s digital world, SBC is a great tool for attracting talent, it has a negative effect on a shareholder’s equity stake in the company and will dilute their ownership over time. Essentially, when employees exercise stock options or receive shares, new shares are introduced into the market which dilutes the ownership stake of each shareholder.

Although, it is a good sign to view free cash flow growth has been outpacing stock-based compensation as of lately. Nevertheless, not only should an investor focus on the quality of a company’s free cash flow but also the amount of stock-based compensation relative to those free cash flows.

Expanding into new market verticals

If a company believes that its reinvestment runway is long but begins to expand into new verticals, it may be a sign that there is little room to grow in its existing runway. This means that, to achieve a certain growth rate target, the company must deviate from its existing verticals into new ones to keep up, despite informing investors that the runway is long.

Another red flag of expanding into new markets is expanding into new products or services outside of management’s circle of competence and outside of the company’s competitive advantage. Not only is the management playing with fire with a lack of knowledge and experience, but they are likely to destroy shareholder value by continuing to expand in this way.

The key to figuring out the success of this expansion is whether it will strengthen the competitive advantage of the company. For example, Apple has lately been expanding its service side of the business with Apple One, iCloud, AppleCare, and other App Store-related offerings. While they have notoriously been known as a hardware company, expanding and improving their service suite reinforces the Apple Ecosystem network effect by making it harder for the average Apple user to leave.

Resources to Help The Investor Get Started

A list of some ‘quality’ superinvestors:

Dev Kantesaria — of Valley Forge Capital Management

Chuck Akre — Akre Capital Management

Francis Rochon — Giverny Capital

Terry Smith — Fundsmith

Nick Sleep — Nomad Investment Partnership

Chris Mayer — Woodlock House Family Capital

Shreekkanth Viswanathan — SVN Capital

We have written a report about Dev Kantesaria and his investment philosophy. We view him as an investor who holds the highest-quality companies and has a very high hurdle rate when approaching business quality. For more information, read here:

Lessons Learned from Superinvestor Dev Kantesaria

All of us investors claim to be investing in what we deem to be the highest quality companies. But is this really the case?

Some books to check out:

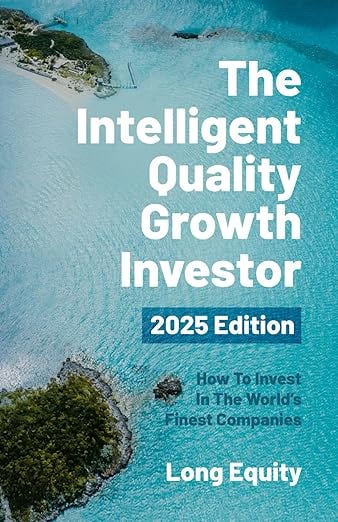

The Intelligent Quality Growth Investor 2025 Edition by Long Equity

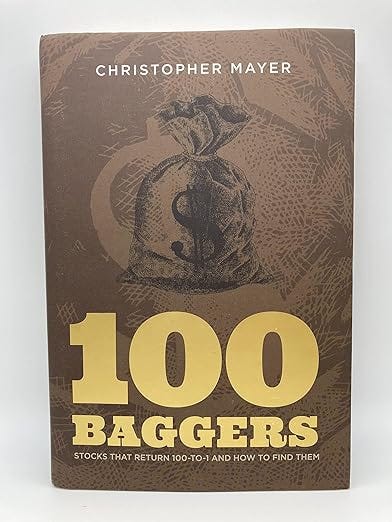

100 Baggers by Chris Mayer

Some videos to watch to get you started:

_________________________________________________________________________

Disclosure: This is not financial advice!

Thanks for reading. I put a lot of hours into completing this deep dive for free, so I would appreciate it if you could subscribe to this Substack and follow me on X/Twitter @Pngfund for more of my insights like this. Cheers!

Excellent breakdown and information!

qarpfund.com